I was born in Upper Silesia, raised among smoking chimneys, winding towers, and the traces of a vanished industrial era. A landscape where medieval towns blend seamlessly into workers’ settlements. Where 19th-century tenements stand beside endless rail lines; where fields are cut by embankments; where slag heaps rise against the horizon, and the sun often hovers above them like a distant, glowing promise.

For the past 35 years, I have lived in a similar space: the Ruhr region. And yet, as much as this environment shaped me, it also drove me to seek something beyond it — into the mountains of the Silesian Beskids, into the High Tatras. To those places where the forests whisper their own stories; where the rustle of leaves and the murmur of the wind create a kind of silence that could never be found in the industrial homeland. Today, I search for that same quiet, that same contrast, in the forests of the Sauerland or the fjords of Norway — places where nature still speaks its ancient language, unchanged.

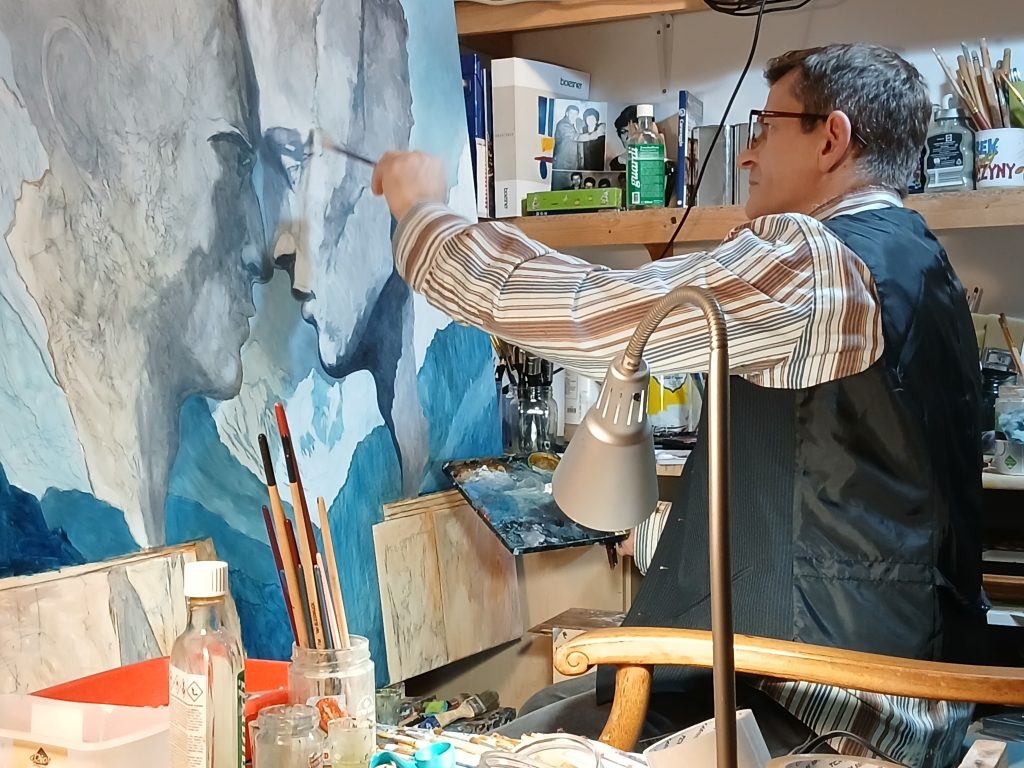

My art was born from this world: from the tension between industry and nature, between human and space, between transience and permanence. Shaped by the industrial atmosphere of Upper Silesia and the Ruhr area, it began with depictions of industrial and post-industrial landscapes, painted in a synthetic style. Later, my focus turned to the human figure — the ultimate masterpiece of creation. Eventually, I found my own voice in a form of magical realism, where the human being stands at the center: a seeker in a world full of riddles, caught between knowledge and infinity.

As a child, I was surrounded by art, but my perception of it has changed over time. I remember standing at the age of ten in a museum in Bytom, in front of Picasso’s drawings — confronted for the first time with an art that reached beyond the visible. My fascination with modernism led me to the old masters — Caravaggio, Vermeer, the Pre-Raphaelites — painters who mastered light and made the soul visible.

Today, my art stands in conscious contrast to the currents of postmodern art — far removed from abstract expressionism, deconstructivism, or conceptual art. It is a return to the narrative, to depth, to mystery. It places the human being at the center — as a creature moving through a world full of secrets.

Exhibitions include:

Silhouettes – La Galerie Art Présent, Paris

Kunstagentur Produkt 17, Cologne

Rififi Kunstkeller, Innsbruck

Cascina Farsetti, Rome – Biennale I colori polacchi a Roma

Silesia, Stuttgart

Entry into the Inner Landscape – a companion exhibition for the world premiere of the play based on Janosch’s Cholonek in Katowice, organized by the House of German-Polish Cooperation in Gliwice

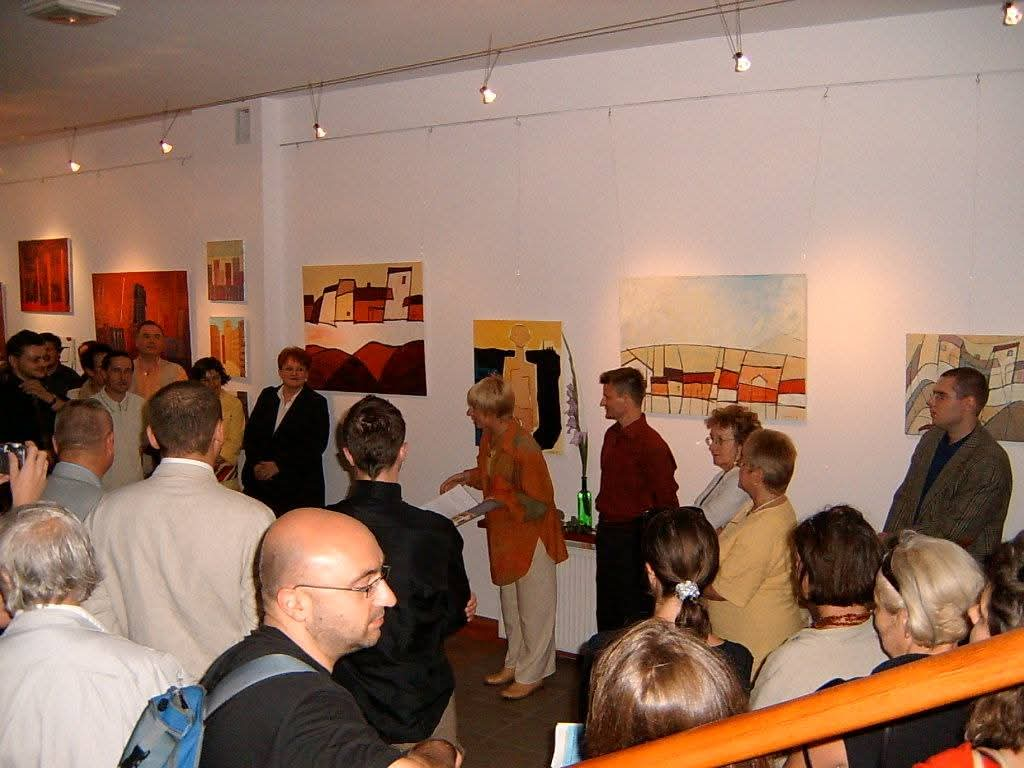

Silesia – Biuro Promocji Bytomia, Bytom, Poland

Biuro Promcji Bytomia

The major exhibition of the “Silesia” series at the Bytom Promotion Office (Biuro Promocji Bytomia) held special significance for me, as someone born in Bytom.

Biuro Promcji Bytomia

The exhibition was accompanied musically by the late Upper Silesian blues musician Jan “Kyks” Skrzek.

Galerie Mozaika

Radzionków is a small mining town in Upper Silesia, and visitors there were able to deeply identify with the synthetic depictions of the Upper Silesian landscapes.

Paris

In 2003, I had the honor of presenting my works from the “Silhouettes” series at Galerie Art Présent in the City of Light, Paris.

Reflections

This exhibition […] is not merely a scenographic supplement or illustration to the theatrical adaptation of Janosch’s novel. Rather, it proposes a contemporary, synthetic view of a landscape that not only shaped and revealed the colors of Cholonek’s world but still forms the living environment of today’s Upper Silesians.

This exhibition is like a small canvas on which a brief film about the contemporary view of Upper Silesia is projected. It leads through the external landscape, which naturally becomes the entrance to the inner world of the play’s characters. And this world is multilayered — like the coal seams in the Bytom mines or the veins of silver beneath Tarnowskie Góry. The codes of meaning embedded in these landscapes demand careful decoding.

In Cholonek, Janosch writes:

“If you didn’t look closely, you could say: Everything is dirty, and the earth is nothing but coal dust. But you could also see it another way and say: How beautifully everything glistens in the sun! You can look at everything this way or that way.”The two painters invite us to take this second perspective as a guide — to see Upper Silesia through the lens of its beauty and its colors. Their paintings do not depict any specific, recognizable panorama or architectural detail. Instead, their works are the result of an inner synthesis of the world around them.

What matters most is color — the fascination with it. Because, as the characters in Cholonek say:

“When the sky looks like a lemon with raspberry juice, you can go mad” — and all you can do is “sit and cry.”House of German-Polish Cooperation (Dom Współpracy Polsko-Niemieckiej), 2004